Rome’s Sweet ‘Pizza’ Is a Symbol of Jewish Perseverance

It’s a crisp spring morning in Rome’s Via del Portico d'Ottavia, the heart of the city’s Jewish Quarter. The neighborhood is slowly waking up. Most shops are still closed, but one part of the street is already bustling. Right outside the local school, at the corner with Piazza Costaguti, a small crowd has lined up outside Boccione, Rome’s oldest bakery. Here, for the past 210 years, the Limentani family has been making kosher treats like almond and cinnamon cookies, sour cherry pies, and pizza Ebraica, literally “Jewish pizza,” one of the bakery’s iconic dishes. If you are conjuring up images of cheese-topped flatbreads, think again. Pizza Ebraica, also known as pizza di Beridde, is a sort of thick cookie that’s filled with almonds, pine nuts, raisins, and candied fruit. Usually served with a blackened, almost-burned crust, the fruitcake-like dish is considered a symbol of Jewish–Roman cuisine. The recipe has been passed down from one generation to the next, says Gioia Limentani, a fifth-generation baker who runs Boccione with her sisters and cousins. “Its roots go back to the arrival of Jewish refugees in Rome after they were expelled from the Kingdom of Spain in 1492,” she says. When asked for more details about the recipe, Limentani pushes back. “It’s a family secret,” she explains. Indeed, many locals like to think of Boccione’s pizza di Beridde as the Coca-Cola of Jewish–Roman cuisine, says Micaela Pavoncello, a native of Rome’s Jewish Quarter who runs tours focused on Rome’s Jewish history. When we speak, a few days before the election of Pope Leo XIV, she jokes, “It’s easier for you to find out who will be the next pope than to get Boccione’s recipe.” Pizza di Beridde takes its name from the Italianized version of the Jewish phrase Brit Milah, which describes the ritual of circumcision. Traditionally, the treat was baked to celebrate this rite, but with time it became a staple of other Jewish festivities like weddings or bat mitzvahs, says Silvia Nacamulli, a Jewish–Roman native who wrote Jewish Flavours of Italy, a cookbook of Italian–Jewish recipes. “In my family we usually make it for the Mishmarah, the evening of prayer and singing held before festivities,” Nacamulli says. “And most families give it as a kavod, a small gift distributed to guests during celebrations.” If baked at home, pizza di Beridde is relatively easy to make, Nacamulli says. The traditional recipe has no eggs or dairy. All you need is flour, sugar, sunflower oil, nuts (such as almonds and pine nuts), raisins, and candied fruit. First, you need to marinate the mixed nuts and candied fruit overnight in white wine. The following day, you add the rest of the ingredients and shape everything into brick-size pieces that are baked in the oven at a high temperature—this is crucial to get the “burned” crust, a signature of pizza di Beridde. The result is a crunchy, cookie-like treat with the subtle sweetness of candied fruits. Also known as pizza di Piazza (literally “pizza of the square”), a reference to Boccione’s location in the main square of Rome’s Jewish Quarter, the cookie has centuries-old roots. “The fact that a sweet treat is called pizza suggests that it is very old,” Nacamulli says. During the Renaissance, she explains, people called almost anything that was baked in an oven “pizza,” from focaccias to cakes. For example, in his 1570 cookbook, Opera dell’Arte del Cucinare, Bartolomeo Scappi uses the word pizza to describe a sweet recipe, while in his 1891 cookbook, Pellegrino Artusi uses the word pizza to describe anything from flatbreads to thick biscotti. It is hard to pinpoint the exact origin of pizza di Beridde. “We can’t say for sure how the pizza originated,” Nacamulli says. “But its key ingredients probably came through trade links and different waves of migrations.” Pine nuts, candied fruits, and almonds were typically used in Sicily, which was under Spanish rule between 1409 until 1713, so Nacamulli says it is likely that Sicilian Jews who flocked to Rome after the expulsion of 1492 took with them what later became the building blocks of pizza di Beridde. But Rome’s Jewish community may have been exposed to those ingredients even earlier, says Sean Wyer, a postdoctoral fellow in Italian at St. Hugh’s College–Oxford and the author of two journal articles on Jewish–Roman cuisine. “Even before the institution of Rome’s [Jewish] Ghetto in 1555 there was a lot of communication between various Jewish communities of the Mediterranean,” he says. “So it’s not impossible that some of the ingredients that become part of pizza di Beridde were available even before the arrival of migrants from Spain and Sicily.” But locals may have a good reason for embracing an origin story that ties the dish to the Jewish expulsion of 1492. “Food can often become a way for people to talk about their heritage,” Wyer says. “Tracing pizza di Beridde back to the arrival of refugees in 1492 is a way to make that story accessible to m

It’s a crisp spring morning in Rome’s Via del Portico d'Ottavia, the heart of the city’s Jewish Quarter. The neighborhood is slowly waking up. Most shops are still closed, but one part of the street is already bustling. Right outside the local school, at the corner with Piazza Costaguti, a small crowd has lined up outside Boccione, Rome’s oldest bakery.

Here, for the past 210 years, the Limentani family has been making kosher treats like almond and cinnamon cookies, sour cherry pies, and pizza Ebraica, literally “Jewish pizza,” one of the bakery’s iconic dishes. If you are conjuring up images of cheese-topped flatbreads, think again. Pizza Ebraica, also known as pizza di Beridde, is a sort of thick cookie that’s filled with almonds, pine nuts, raisins, and candied fruit. Usually served with a blackened, almost-burned crust, the fruitcake-like dish is considered a symbol of Jewish–Roman cuisine.

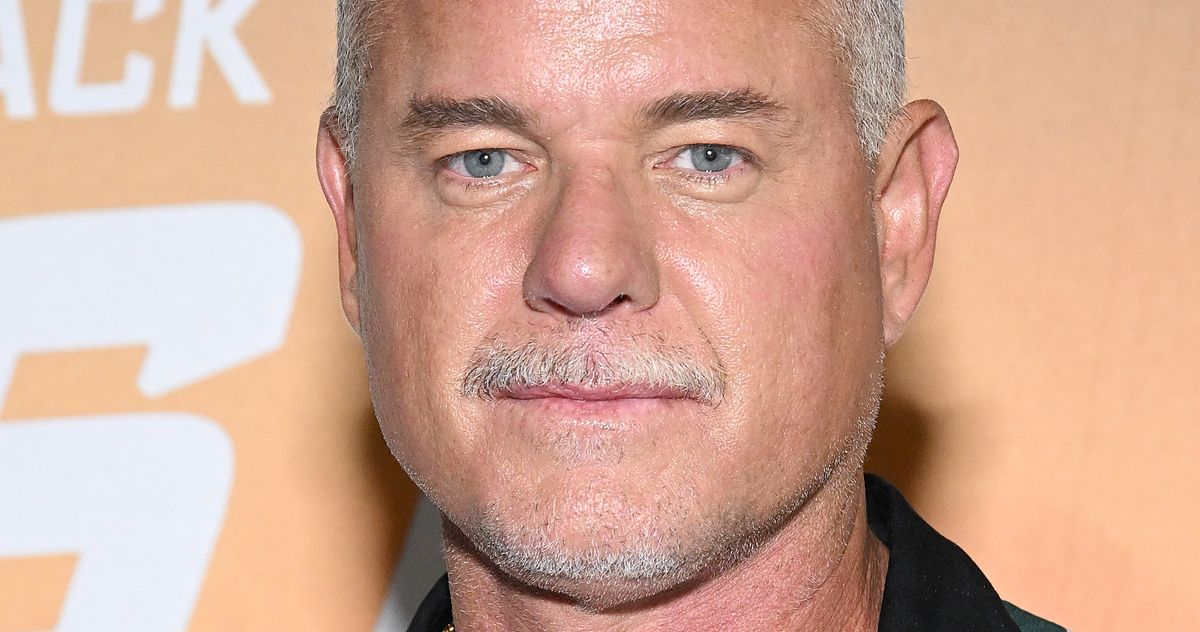

The recipe has been passed down from one generation to the next, says Gioia Limentani, a fifth-generation baker who runs Boccione with her sisters and cousins. “Its roots go back to the arrival of Jewish refugees in Rome after they were expelled from the Kingdom of Spain in 1492,” she says. When asked for more details about the recipe, Limentani pushes back. “It’s a family secret,” she explains. Indeed, many locals like to think of Boccione’s pizza di Beridde as the Coca-Cola of Jewish–Roman cuisine, says Micaela Pavoncello, a native of Rome’s Jewish Quarter who runs tours focused on Rome’s Jewish history. When we speak, a few days before the election of Pope Leo XIV, she jokes, “It’s easier for you to find out who will be the next pope than to get Boccione’s recipe.”

Pizza di Beridde takes its name from the Italianized version of the Jewish phrase Brit Milah, which describes the ritual of circumcision. Traditionally, the treat was baked to celebrate this rite, but with time it became a staple of other Jewish festivities like weddings or bat mitzvahs, says Silvia Nacamulli, a Jewish–Roman native who wrote Jewish Flavours of Italy, a cookbook of Italian–Jewish recipes. “In my family we usually make it for the Mishmarah, the evening of prayer and singing held before festivities,” Nacamulli says. “And most families give it as a kavod, a small gift distributed to guests during celebrations.”

If baked at home, pizza di Beridde is relatively easy to make, Nacamulli says. The traditional recipe has no eggs or dairy. All you need is flour, sugar, sunflower oil, nuts (such as almonds and pine nuts), raisins, and candied fruit. First, you need to marinate the mixed nuts and candied fruit overnight in white wine. The following day, you add the rest of the ingredients and shape everything into brick-size pieces that are baked in the oven at a high temperature—this is crucial to get the “burned” crust, a signature of pizza di Beridde. The result is a crunchy, cookie-like treat with the subtle sweetness of candied fruits.

Also known as pizza di Piazza (literally “pizza of the square”), a reference to Boccione’s location in the main square of Rome’s Jewish Quarter, the cookie has centuries-old roots. “The fact that a sweet treat is called pizza suggests that it is very old,” Nacamulli says. During the Renaissance, she explains, people called almost anything that was baked in an oven “pizza,” from focaccias to cakes. For example, in his 1570 cookbook, Opera dell’Arte del Cucinare, Bartolomeo Scappi uses the word pizza to describe a sweet recipe, while in his 1891 cookbook, Pellegrino Artusi uses the word pizza to describe anything from flatbreads to thick biscotti.

It is hard to pinpoint the exact origin of pizza di Beridde. “We can’t say for sure how the pizza originated,” Nacamulli says. “But its key ingredients probably came through trade links and different waves of migrations.” Pine nuts, candied fruits, and almonds were typically used in Sicily, which was under Spanish rule between 1409 until 1713, so Nacamulli says it is likely that Sicilian Jews who flocked to Rome after the expulsion of 1492 took with them what later became the building blocks of pizza di Beridde.

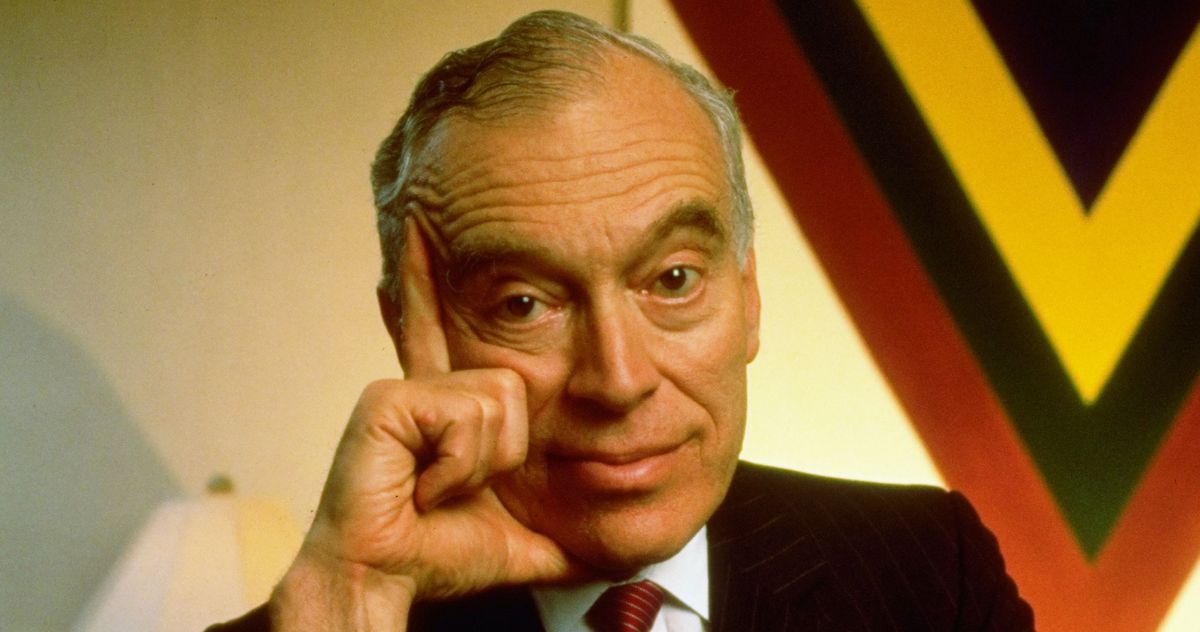

But Rome’s Jewish community may have been exposed to those ingredients even earlier, says Sean Wyer, a postdoctoral fellow in Italian at St. Hugh’s College–Oxford and the author of two journal articles on Jewish–Roman cuisine. “Even before the institution of Rome’s [Jewish] Ghetto in 1555 there was a lot of communication between various Jewish communities of the Mediterranean,” he says. “So it’s not impossible that some of the ingredients that become part of pizza di Beridde were available even before the arrival of migrants from Spain and Sicily.”

But locals may have a good reason for embracing an origin story that ties the dish to the Jewish expulsion of 1492. “Food can often become a way for people to talk about their heritage,” Wyer says. “Tracing pizza di Beridde back to the arrival of refugees in 1492 is a way to make that story accessible to many people.”

Jewish cuisine and local Roman cuisine are so intertwined that it’s almost impossible to distinguish one from the other, Wyer adds. Rome’s Jewish community, one of the longest-standing Jewish communities in Western Europe, has been based in the Italian capital since at least the second century BC. Over the course of more than 2,000 years, they’ve left a profound mark on Roman cuisine. “Foods that are now considered staples of Roman gastronomy like baccalà fritto [fried codfish] or carciofi alla giudia [fried artichoke] were introduced by the Jewish community,” Wyer says. “Almost any Roman dishes fried in oil have Jewish roots—Jewish people were forbidden by kashrut rules to use lard, which was the most common fat for cooking until the 1900s.”

For many local Jews, these dishes have become a symbol of identity in the face of oppression. According to Pavoncello, the tour guide, Jewish civil rights in Rome changed drastically across time depending on the policies of different Roman rulers. The strongest restrictions were put in place by Pope Paul IV, who established the city’s Jewish Ghetto in the area that surrounds Via Portico d’Ottavia. “The pope’s strategy to convert Jewish people was much more subtle than that of other European rulers of that time,” Pavoncello says. “While the King of Spain expelled the Jews, the pope made their life really hard, hoping that they would eventually convert.”

While Jews were allowed to observe Shabbat, they were also forced to attend Mass on Sundays. A painting inside Rome’s Jewish Museum shows a group of Jewish people sitting in a church, looking distracted or asleep, guarded by the pope’s police. The Roman dialect expression darte na sveja (“waking you up”) traces back to the practice of using bells to keep Jewish people awake during compulsory Mass, Pavoncello says.

The Ghetto was finally dismantled when troops from the newly declared Kingdom of Italy seized Rome in 1870, ending approximately 1,000 years of papal rule. After annexation to the Italian Kingdom, the city’s Jewish community enjoyed 70 years of freedom, becoming well integrated into public life. Jewish people, who could finally reside in any part of the city, enjoyed full religious freedom without constraints like compulsory Mass attendance. Many Jewish professionals took on prominent roles in society as doctors, bankers, or military leaders. This freedom lasted until the notorious racial laws of 1938, when Jewish children were expelled from school, interfaith marriages were banned, and Jewish men could no longer serve in the army. The culmination of Fascist oppression against the local Jewish community happened on October 16, 1943, when Italian and German troops kidnapped more than 1,200 Jewish people from Rome’s Jewish Quarter and deported them to Auschwitz.

“They came and took all the men,” says Boccione’s Gioia Limentani, whose great-grandfather was deported and killed. “So at the end of the war, the only one left to preserve our centuries-old bakery was our grandmother.” Since then, the female descendants of Limentani’s grandmother have kept baking cookies, ciambellette, and pizza di Beridde following their family recipes. “For a community that has endured restrictions, oppression, and deportation, food and recipes are a powerful way to connect with previous generations and keep identity alive,” Pavoncello says.

Today, Boccione is seen as a quintessential symbol of Roman–Jewish identity. And, in a funny twist of fate, it is not uncommon for Catholic priests to seek out pizza Ebraica, reportedly a favorite of the former Pope Benedict XVI. “Sometimes you’ll spot priests in line at Boccione,” Wyer says. “It really says a lot about the way in which local culture evolved.”

Explore more of the world’s culinary wonders with Gastro Obscura’s second annual Feast, a series of guides, stories, and recipes from our top six dining destinations of the year.

.jpg)