Artist Kennedy Yanko Is Taking Up Space—And She's Doing It On Her Own Terms

The innovative sculptor and installation artist opens up to L'OFFICIEL about finding inspiration, her latest exhibitions in New York City, and channeling creative energy through her style.

PHOTOGRAPHY Seleen Selah

STYLING Kate Housh

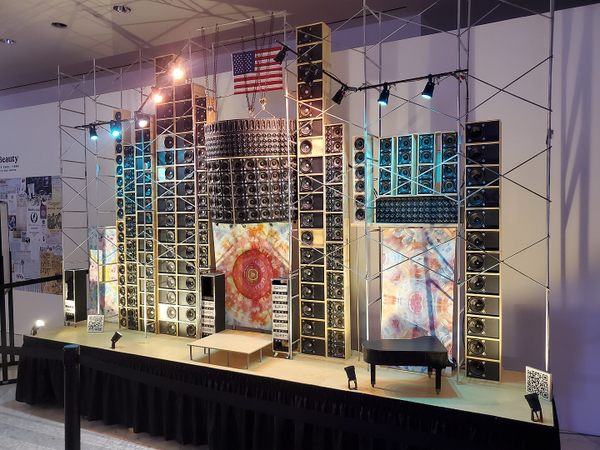

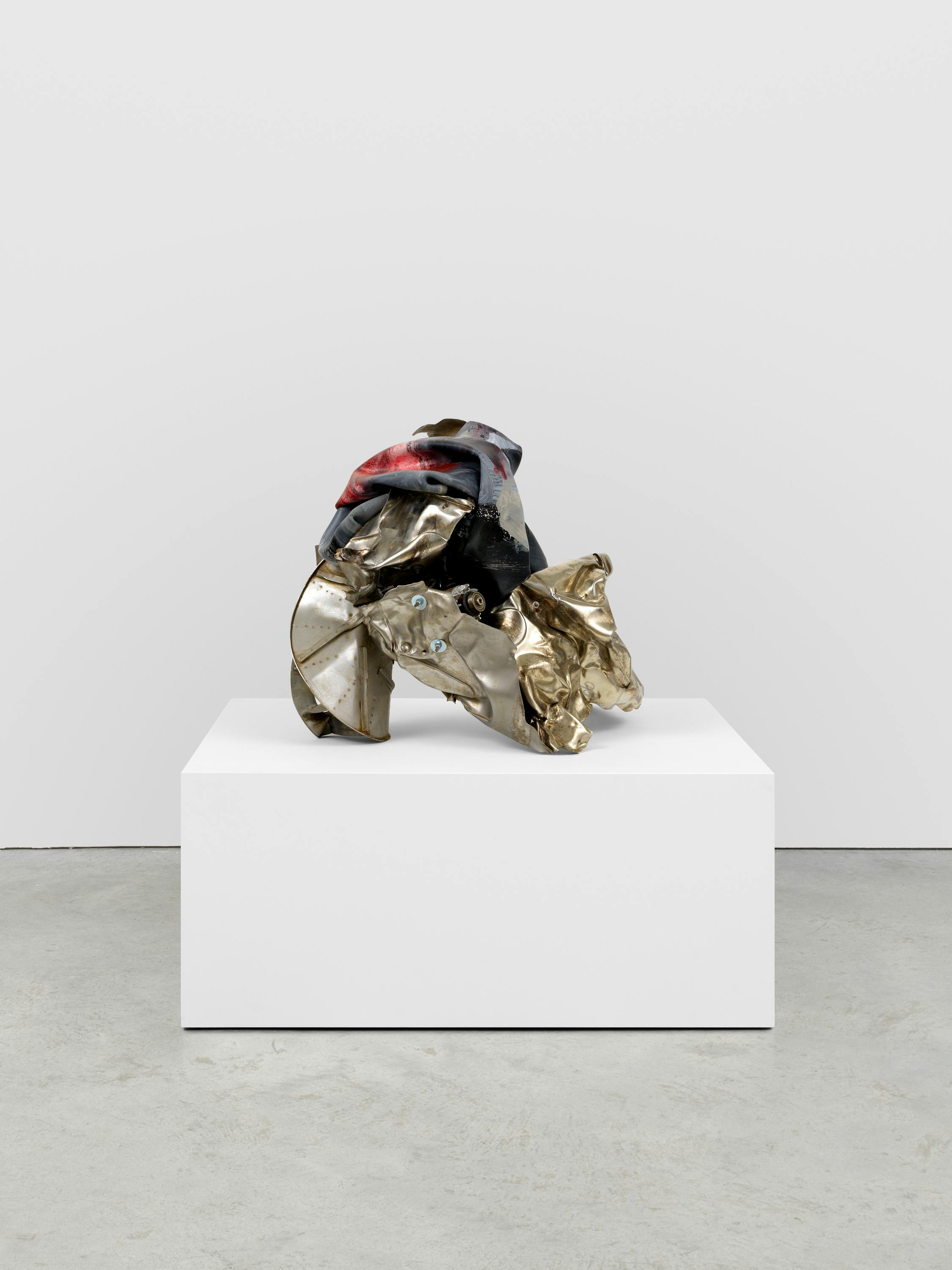

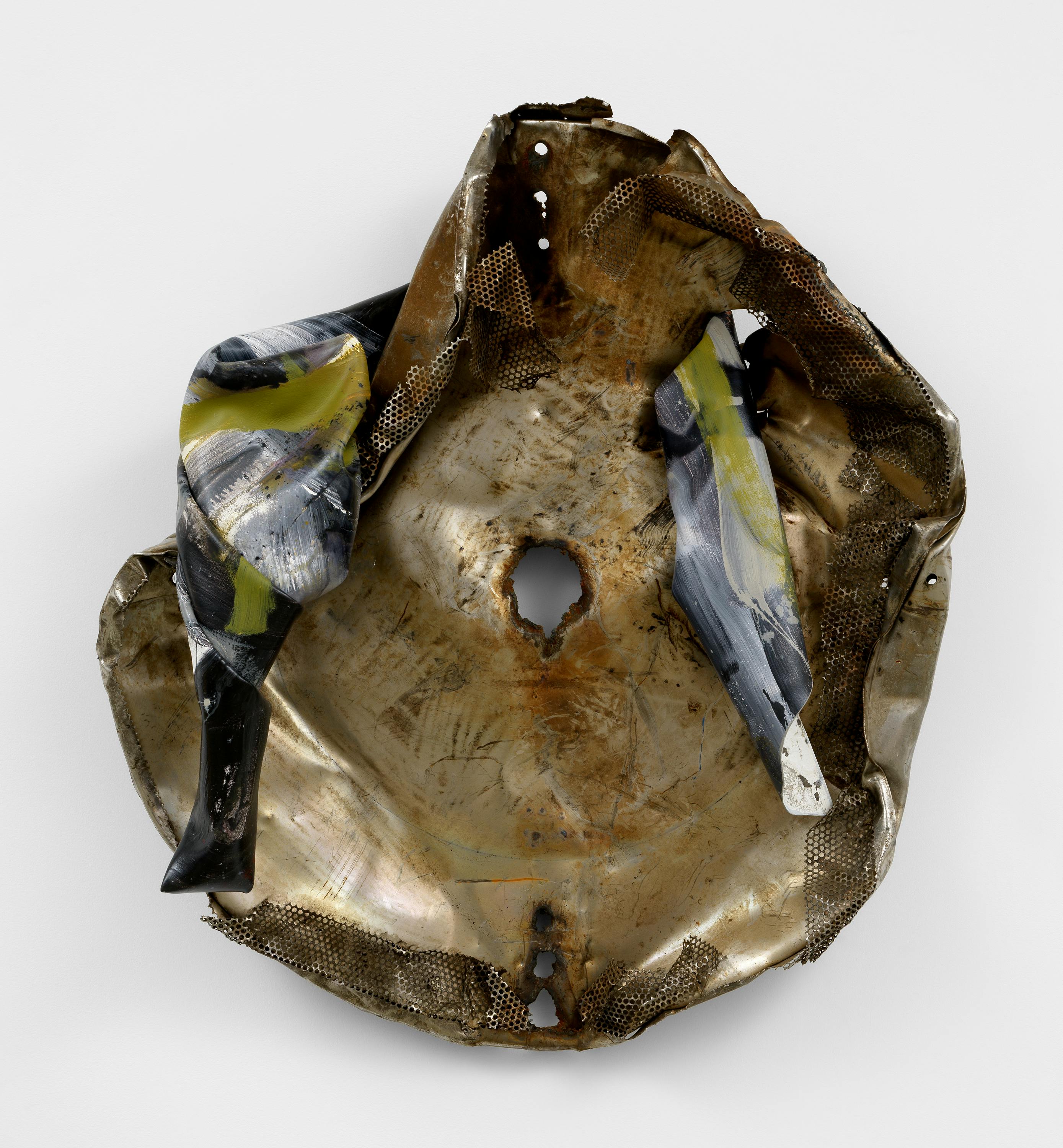

“I'm fascinated by how artists translate the world through materials,” says Kennedy Yanko. As a three-dimensional sculptural painter, the 36-year-old St. Louis-born artist has made a name for doing this very thing herself. Ever since she first burst onto the scene with her installations—composed of found metal and paint, which she uses as a skin-like material—she’s gone on to show everywhere from Miami’s Rubell Museum (she was the 2021 Artist in Residence) to Switzerland’s Art Basel to the Brooklyn Museum. She recently returned to New York, making her mark on Manhattan with two exhibitions: Retro Future—a three-story exploration of color, expression, and form through sculptural painting—at Salon 94 on the Upper East Side (through May 17), and Epithets, featuring new work centered on “the architecture of language and the power of invocation” at James Cohan in Tribeca (through May 10).

For Yanko, the latter exhibit was particularly personal. “Epithets draws from a very deep, guttural place in me that translates internal landscapes into an outward physical form,” she tells L’OFFICIEL. “It was very cathartic, to intentionally create a moodier and heavier body of work, which reflected what I had been processing this past year myself. It’s been gratifying to see that emotional and psychic depth come through in the work, especially given how responsive my practice is to the materials themselves.”

Yanko’s work is all about energy, and it’s her chosen materials that allow her to play between the realms of the surreal and the earthbound. “I think a material holds energy and information beyond its surface,” she says, explaining that the 2021 show she curated for Chicago’s Kavi Gupta Gallery, called Surface is Only A Material Vehicle for Spirit, “deeply shaped” her thoughts on the subject. “To me, material is really just a vessel for invisible forces—that's the earthbound part. The surreal aspect comes from challenging perception, like the reminder that what we can see isn't always what it seems. The paint skins embody that: They look almost like folded fabric or lush organic matter, but they are pure paint, suspended in three dimensions.”

Although she began working in the three-dimensional space with paint over a decade ago, it wasn’t until Yanko started bringing metal into her work that she felt she’d found her calling—even if she didn’t exactly understand the logistics of her method at the time. “I didn’t know how I was going to keep this paint skin on the sculpture; I just kind of threw it on there and got a picture of it,” she recalls. “Just taking that risk felt so revelatory and cool. I had gotten to a place where painting was not it. The canvas, the square box…it was just not doing it for me.”

Now, Yanko is known for quite literally thinking outside of the box—and she’s celebrating how far she’s come. “I lived in New York for 15 years, but this moment feels like I'm sharing different, fully realized parts of myself and my practice within the city,” she says. “It’s both the closing of one chapter and the beginning of another.” Read our full conversation below about navigating oversaturation in the art world, wanting people to experience her work IRL, and finding her voice in the industry.

L’OFFICIEL: First of all, congratulations on two incredible shows. What first inspired you to get into art?

KENNEDY YANKO: I've always been a painter and I've always worked in abstraction. But my early compositions were about forms and energy and gestures and that are very still present today. Some of the people that I was looking at were Abstract Expressionists—especially post World War II work—and Surrealists. I was fascinated by how they worked with the subconscious to create form. Even in the sixth grade, I was really drawn to Jackson Pollock.

L’O: Is there one piece from Epithets or Retro Future that’s particularly important to you?

KY: For me, one of the most meaningful pieces is a hanging work that I created for Retro Future called “Jetstream Dreams.” It captures the feeling of metal suspended in space, and it was made during a time when there were all of these frequent plane crashes at once. It reflects the fragility of suspension.

L’O: Your work is all about energy. What kind of energy do you try to call into your life?

KY: Repetition. Consistency. Focus. But really, intention is what leads energy. When I used to practice Qigong [a system of coordinated body movements, breathing, and meditation rooted in Chinese medicine], my Sifu [or teacher] would always say, The Yi leads the Qi. The Yi is intention [and the Qi is the body’s vital energy or life force], so holding a clear intention is central both to my interactions and to my making.

L’O: What do you think surprises people most about your work?

KY: I think a lot of people experience my work through their phones or through photographs on a screen, and when they actually get to see the work in person, there's a lively quality to it where it almost feels like it's moving or it's breathing. I think that's what makes it so significant. Photos of my work are the bane of my existence, because sculpture is all about engaging with it—walking up to it and moving around it. Every single side has a different face. It's a very experiential kind of work.

L’O: How often do you look at a piece of art and feel connected to it?

KY: I've been around art my whole life, and I find that truly profound experiences with art are very rare. They don't happen every day. In today's oversaturated art world, people expect epiphanies and real connections to art, when it’s something that may only happen once a year, if you're lucky. I think it's important to recognize the rarity and preciousness of those moments.

L’O: Given the—as you put it—oversaturation of the art world, do you think it’s even harder to find pieces that make us truly feel something?

KY: It's such a personal thing. Right now, in the art world, things are shifting because it is so oversaturated. There's so much art. There's kind of, like, a purge that's happening. So I think it's about listening to your gut; think of it the same way you would pick your best friends. When you’re really called to something, you engage with it in a big way. Your hair stands up on your arms. That's the only way to judge if something's good or bad. Even if it's not a piece that you're generally pulled to, but there's something there, take the time to go read about the concept or the artist before you really form an idea around it.

L’O: What are you typically drawn to?

KY: I'm a materialist, so I’m always looking for the inventiveness of materiality. It's the execution of it, the overall visual language, and the sensation that the artist is creating. That’s what I'm really interested in. I think materialists like Hugo McCloud, Hugh Hayden, Leonardo Drew, Anselm Kiefer, and Mark Bradford are creating really powerful work.

L’O: Has any artwork recently caught your own eye?

KY: The Jack Whitten show at MoMA. This man is a religion and a god. When you look at the titles of his work, it's listed as acrylic and canvas. But he was working in paint skins in a way, because he was [creating abstract paintings using hardened paint] that was built into tiles, and then he’d chop them up into little pieces. It makes me sad to think about what this man contributed to art and history, and how little attention and celebration he got during his lifetime. And not only that, but just in his language and what he's created in [the collection of his writings] Notes from the Woodshed, and the way he describes the ideas of consciousness and being through materiality in such a special and simple way… that’s something I hope to further and challenge myself.

L’O: What do you think is your own most profound piece, to date?

KY: I'm very proud of my work at the Rubell Museum. Those pieces were my first time really getting to work at scale, and I love them. They opened up a door—and an entire world—for me, to work in a whole new way as an artist. Now I’m ambitious for scale expansion. I’m always looking at space and figuring out how to move—and take up space—within it.

L’O: What do you hope people feel when they look at a piece of your work?

KY: I just hope they feel something—anything—real. And I hope my work reminds people of the power of presence, and the possibilities that can emerge from nurturing the inner world in the outer world.

L’O: In the very chaotic world that we live in, what keeps you inspired?

KY: Rest is absolutely essential to me, so taking real time to rest. And to research, read, and very much live life fully. Being in nature is really important to me. Water is a very regular tool that I use, being in the sun. Traveling refills me a lot. And I think, ultimately, spending time with my fellow artists is a major source of inspiration. I think when I'm totally empty, when I have nothing to give and can't even give my art something, I'll find myself in studios. That's a sacred, special place.

L’O: The art world can be notoriously difficult to break into. Since you’ve been in the industry, how have you seen the shift, between the old guard and the new guard?

KY: It's cool to see how, generationally, things get turned over. Because then your generation becomes the thing. I'm seeing my friends and the people who resonate with me become directors of museums and head curators, and artists that I know are having institutional shows. It’s incredible. But artists really need proper support in their businesses to support their practices. It's nice to see a little bit more openness around other ways of making money, like working with brands. People are a bit more open to things they might not be used to, in terms of what an artist looks like or how they present. That was something I always struggled with, being a very femme-presenting woman. I'm in my clothes and I'm loud; this is how I move. I don't think academia was very interested in that. It was hard for them to listen to me.

L’O: Was that the biggest challenge that you’ve faced in the industry? Being perceived a certain way or not being taken seriously because of how you look?

KY: Yeah, definitely. It's really about getting people to close their eyes and listen.

L’O: Do you channel your creative energy in the way you dress?

KY: It's such a powerful thing, because when you change your outfit, it changes so much about how you feel and what you're capable of and what you want to do. The clothes that I choose really are dependent on how I want to feel, what I want to do, and what kind of place I want to be in. My body is very sensitive, and I'm also a very visual person. So, my style is very responsive to what bitch I want to be that day.

HAIR AND MAKEUP Estaban Martinez