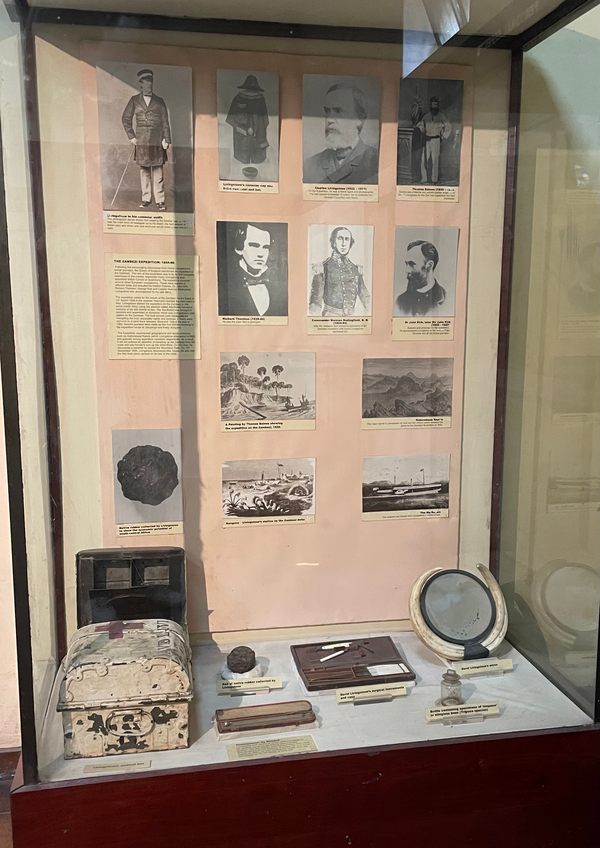

David Livingstone’s Shaving Mirror in Livingstone, Zambia

Appropriately, at the heart of the sprawling Livingstone Museum is a room dedicated to its namesake festooned with curious relics. Among the collections of letters and enthralling exhibits of tales of adventure is an assortment of Livingstone’s personal effects which inspire reflection. His tusk-framed shaving mirror, in particular, reveals the character of one of the Victorian era’s most famous explorers, missionaries, and champions of abolitionism. Unusually curious and disciplined as a child, Livingstone’s upbringing by an austere father engendered a principled perseverance in all things. But it was Livingstone’s compassionate mother who instilled in him a dedication to cleanliness and attention to his appearance. When Henry Morton Stanley traveled with him across the Congo following their legendary 1871 meeting, he noted Livingstone’s immaculate standards, remarking to his men that he “shaved every day of the four months I was with him in the field.” Stanley subsequently required his men to also shave every day, a custom which he himself followed religiously. A complicated and controversial historical figure, Stanley attended to his appearance throughout his life as a sign of self-respect, possibly owing to the grim and degrading childhood he endured. Maintaining order in the midst of chaos was an obsession, and his wife, Dorothy, once recalled, “He had often told me that, on his various expeditions, he had made it a rule, always to shave carefully. In the Great Forest, in ‘Starvation Camp,’ on the mornings of battle, he had never neglected this custom, however great the difficulty.” Such pertinacity, embodied in the spirit of Livingstone’s shaving mirror, perhaps explains why one can hardly travel anywhere in southern Africa without encountering the influence of either Livingstone or Stanley. Compounding that spirit is the mirror’s frame made from the tusks of a warthog, an animal which in folklore represents not only intelligence and commanding presence, but also the ambition of wanderers. And one will need ambition and perseverance while wandering through the extensive collections of the Livingstone Museum, for there is far more on display than can be comfortably absorbed in a single visit. Whether it’s the copious historical collections, anthropological exhibits, natural history displays, or ethnographic offerings, the museum will keep any visitor in rapt attention for hours. Anyone visiting Victoria Falls will be within a whisker of the Livingstone Museum, but travelers shouldn’t bristle or get in a lather over taking time away from the falls to visit the museum—since it is truly a cut above.

Appropriately, at the heart of the sprawling Livingstone Museum is a room dedicated to its namesake festooned with curious relics. Among the collections of letters and enthralling exhibits of tales of adventure is an assortment of Livingstone’s personal effects which inspire reflection. His tusk-framed shaving mirror, in particular, reveals the character of one of the Victorian era’s most famous explorers, missionaries, and champions of abolitionism.

Unusually curious and disciplined as a child, Livingstone’s upbringing by an austere father engendered a principled perseverance in all things. But it was Livingstone’s compassionate mother who instilled in him a dedication to cleanliness and attention to his appearance. When Henry Morton Stanley traveled with him across the Congo following their legendary 1871 meeting, he noted Livingstone’s immaculate standards, remarking to his men that he “shaved every day of the four months I was with him in the field.”

Stanley subsequently required his men to also shave every day, a custom which he himself followed religiously. A complicated and controversial historical figure, Stanley attended to his appearance throughout his life as a sign of self-respect, possibly owing to the grim and degrading childhood he endured. Maintaining order in the midst of chaos was an obsession, and his wife, Dorothy, once recalled, “He had often told me that, on his various expeditions, he had made it a rule, always to shave carefully. In the Great Forest, in ‘Starvation Camp,’ on the mornings of battle, he had never neglected this custom, however great the difficulty.”

Such pertinacity, embodied in the spirit of Livingstone’s shaving mirror, perhaps explains why one can hardly travel anywhere in southern Africa without encountering the influence of either Livingstone or Stanley. Compounding that spirit is the mirror’s frame made from the tusks of a warthog, an animal which in folklore represents not only intelligence and commanding presence, but also the ambition of wanderers.

And one will need ambition and perseverance while wandering through the extensive collections of the Livingstone Museum, for there is far more on display than can be comfortably absorbed in a single visit. Whether it’s the copious historical collections, anthropological exhibits, natural history displays, or ethnographic offerings, the museum will keep any visitor in rapt attention for hours.

Anyone visiting Victoria Falls will be within a whisker of the Livingstone Museum, but travelers shouldn’t bristle or get in a lather over taking time away from the falls to visit the museum—since it is truly a cut above.

![Anime Rangers X Tier List [UPDATE 1] – All Legendary, Mythic, Secret, and Ranger Units Ranked](https://www.destructoid.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ultimate-anime-rangers-units-tier-list.webp?quality=75)