How 'The Phoenician Scheme' Reinvents the Wes Anderson Archetype

Wes Anderson redefines his cinematic style with The Phoenician Scheme, a film that delves into spirituality and the complexities of a father-daughter relationship.

Note to reader, spoilers ahead.

Wes Anderson steps into markedly unfamiliar territory with his new work, The Phoenician Scheme—not by abandoning his signature aesthetic grammar, but by recontextualizing it in a register of restraint. The result is a film that feels less like it flourishes stylistically and serves like a philosophical turning point—a quiet destabilization of his own mythology. It is austere where his films are usually ornate, melancholic rather than arch, and stripped of the nested structures and winking irony that once made his cinema feel untouchable. What emerges is a strange, somber object: an introspective film that retools Anderson’s stylistic tics into something harder to categorize, and harder still to dismiss.

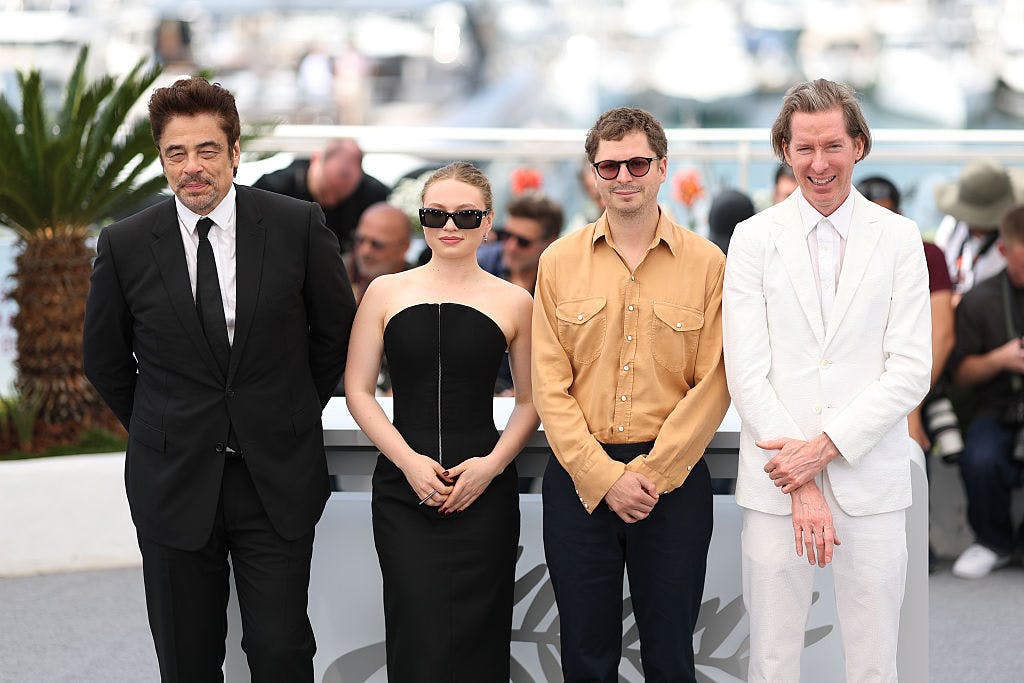

The narrative orbits Anatole “Zsa-Zsa” Korda, an eccentric titan of industry, drifting somewhere between satire and tragedy. Played with a disarming blend of menace and charm by Benicio del Toro, Korda is a man entangled in both empire and entropy. The setting, split between palazzos and fictional nations, lends the film the texture of a historical fever dream.

Does this reinvention mark the beginning of a new chapter in Anderson's career, a singular stylistic departure, or perhaps a Wes Anderson-ized reflection on the state of the world?

The Phonecian Scheme Visuals: Subdued Color Palette and Melancholic Design

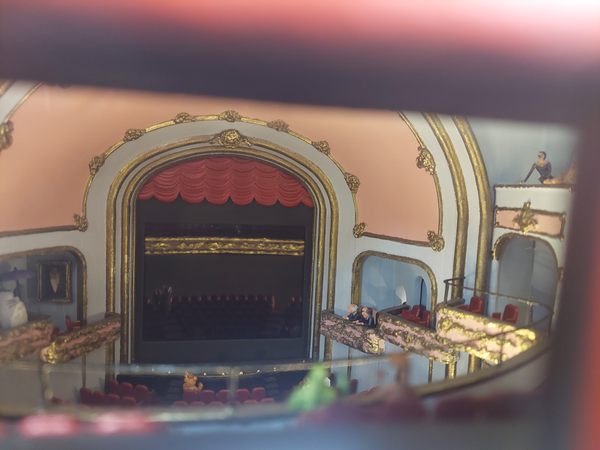

What distinguishes The Phoenician Scheme is not its geopolitical intrigue or postwar pageantry. It’s the stark way the film internalizes them. Anderson departs from his vast worldbuilding, allowing the scenes to unfold with a newfound spaciousness. The compositions are sparse, the palette sun-bleached, the pacing slow enough to feel at times suspended. Gone is the intricate visual pastiche of The Grand Budapest Hotel or Moonrise Kingdom the director has become synonymous with.

Is this evolution or aberration for the director? While his diorama-like compositions and meticulous framing remain, they carry a different weight in the new movie. They are less decorative, as if questioning the very world they once so confidently constructed. Some critics have celebrated the film’s restraint; others argue its minimalism bleeds into the story, leaving behind something tepid, even hollow. One critic from Time said, "There’s something somber about it; it hints at a fringe of exhaustion on Anderson’s part, though it doesn’t seem that he’s tired of movies—more that he’s a little tired of the world." Yet no matter where one lands, it’s undeniable that The Phoenician Scheme marks a directorial pivot.

Religion: A New Motif for Anderson

Perhaps the film’s most unexpected turn is its quiet spiritual undercurrent. Where Anderson often avoids religious undertones, The Phoenician Scheme lets it settle in with an almost fragile seriousness. Zsa-Zsa’s near-death experience—shot in hushed black-and-white—doesn’t promise salvation, only a stark confrontation with mortality.

Anderson, typically guarded by wit and cerebral distance, edges toward something more vulnerable. The film doesn’t offer answers, but it lingers on questions of belief, legacy, and the possibility of something beyond control. It doesn’t preach or resolve—it simply opens a door. Whether that door leads to sincerity, satire, or something more ambiguous is left, compellingly, unanswered.

The Influence of the Personal

The central relationship between Zsa-Zsa and his daughter Liesl (a standout performance by Mia Threapleton) binds the film’s political and personal strands. Their dynamic is one of unspoken damage, structured around legacy, suspicion, and spiritual dislocation. Liesl, a novice nun reluctantly summoned into her father's imperial designs, becomes both successor and moral witness. This isn’t just literary framing—it’s lived memory. The emotional gravity of the father-daughter bond reportedly draws from Anderson’s own experience observing the relationship between his wife and her father. That specificity, passed through the filter of stylization, gives the story its internal resonance. It’s a personal parable coded in spectacle.

Anderson’ collaborators—Roman Coppola, del Toro, and others—each brought their own paternal lens to the film, threading the project with a shared emotional frequency. What could have been a cold satire of geopolitical vanity instead becomes a portrait of aging men haunted by their legacies and the daughters who might forgive or outgrow them. Anderson told the BBC, “So parts of my life went into this one. Roman Coppola has a daughter, Benicio has a daughter. It's something that connected all of us and I think that's how it got into the centre of the film.”

Is this the beginning of a new creative chapter, a one-time shift in tone, or simply an Anderson-esque meditation on the complexities of modern life? Whether this marks a new beginning in Wes Anderson’s career or simply an atmospheric anomaly remains to be seen. But what’s clear is that The Phoenician Scheme expands the emotional and philosophical bandwidth of his work. It suggests that within even the most codified cinematic universes, something uncertain, unresolved, and profoundly human can still be unearthed.

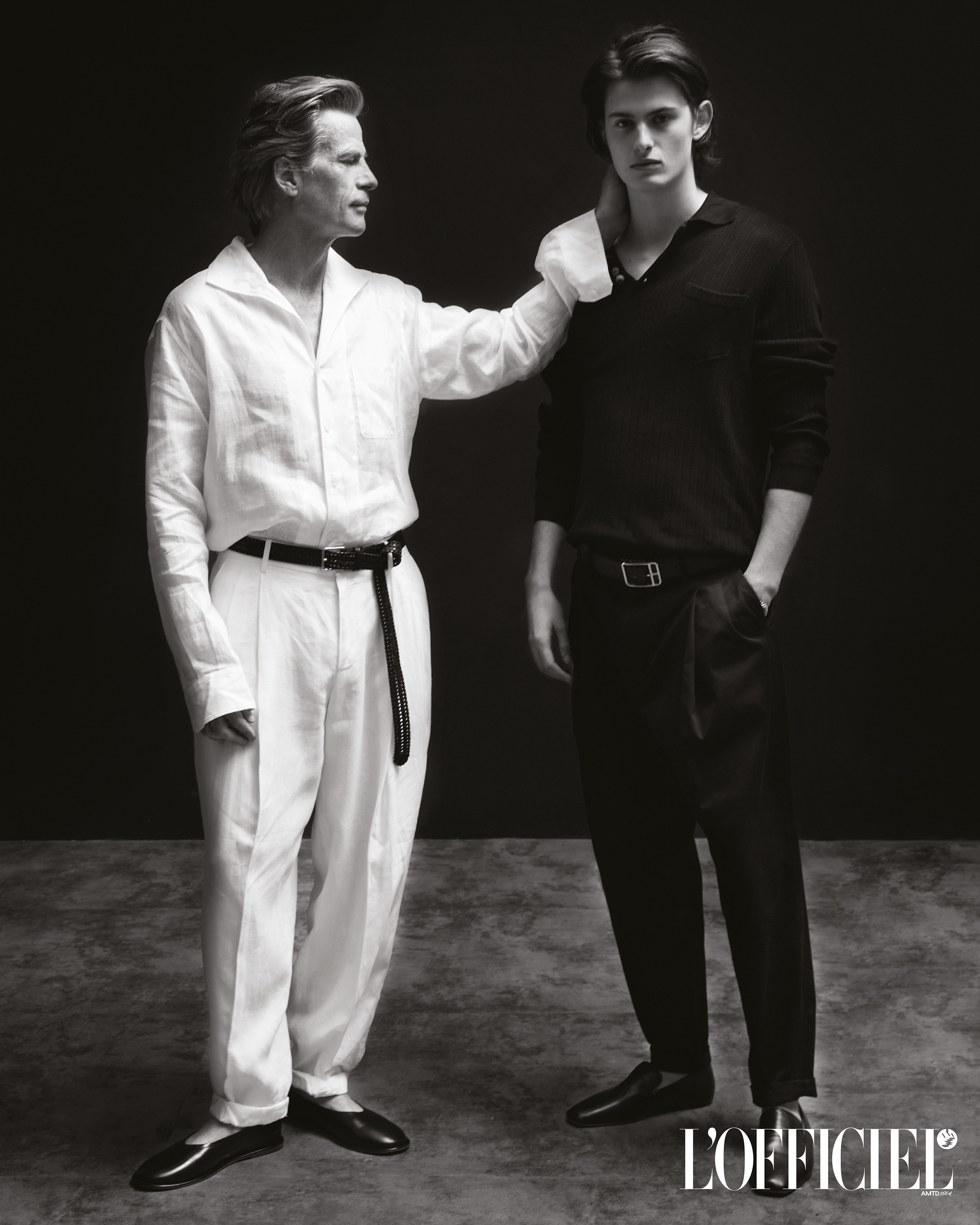

.jpg)

.jpg)