How the ‘Su Filindeu’—or ‘Threads of God’—Pasta Recipe Was Almost Lost to Time

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. What if I told you there was a pasta so special that for more than 300 years pilgrims on the Italian island of Sardinia have trekked 20 miles through the dark just to have a single bowl? What if I told you this pasta was so fiendishly complicated to make that it’s thwarted celebrity chefs and the world’s biggest pasta company? For generations, the art of how to make su filindeu, or threads of god, has been a closely guarded secret. Only women in the small city of Nuoro were allowed to learn this craft. Each mother would teach her daughter how to make these mysterious noodles. But as so often happens with things over the generations, the number of women who possess this particular knowledge has dwindled. A few years ago you could count all of them on one hand. It looks like the threads of god might vanish forever. I’m Johanna Mayer and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Today, the story of the world’s rarest and most mysterious pasta. What it is, why it is so sought after, and what might save it from extinction after this. I’m here today with Diana Hubbell. She’s a reporter for Atlas Obscura and she wrote a piece about su filindeu. Diana, hello. Welcome back. “Hi, happy to be here and talking about my favorite subject, which obviously is noodles.” Obviously. So tell me about these noodles. What exactly is su filindeu? “Su filindeu, which literally translates as ‘threads of god’ in Sardo—which is actually closer to Latin than it is to modern day Italian—it’s this type of incredibly fine hand-pulled noodle. If you’ve seen Chinese chefs make Lanzhou-style ramen, the process actually looks weirdly similar. The cook kneads out a ball of dough until elastic, then stretches it out between their hands, then loops it back over and stretches it again. So, you go from two strands to four to eight, all the way up until 256 strands.” Do we know, is there any significance to that 256 number or is it just like the next time they pulled it, it all broke apart? “I wish I had a more satisfying answer, but I’m pretty sure that when they tried to double it again, just—there was no hope.” That was the breaking point, yes. It feels like there must be some sort of secret Sardinian magical ingredient that keeps these strands from breaking. “So, I was convinced of that going into this story, but it is really just semolina flour, water, and sea salt. There’s no eggs, there’s no special flour. “And for context, su filindeu makes angel hair look chunky. These are thicker than a human hair, but not by a lot. So you can sort of picture it better. This is not just the world’s thinnest spaghetti. Because I think if you just boiled these incredibly long, thin noodles as they are, they would just disintegrate. They’re so fragile. “So what they do is they stretch them all out and they lay them over this huge wooden disc called a fondo. And then they take the next batch of 256 and they stretch it crisscrossed atop. And then they allow that to dry together in the sun and then break it all into shards. “The final result looks almost like this ethereal, super delicate version of Chex Mix.” That sounds good, honestly. Texturally, I imagine—sort of chewy. “Slight factual note. It’s so thin, it’s actually very wispy. It almost dissolves in your mouth.” It’s not chewy? “Not chewy.” Okay. Noted. I stand corrected. And so this is what Christian pilgrims are walking 20 miles through the night to eat. “Yep. Twice a year on the Feast of San Francesco, they walk from Nuoro to the village of Lula. And to celebrate their devotion when they arrive, they’re given a warm foot bath and a bowl of this beautiful handmade pasta at the end of their journey.” And it’s served super simply, right? Is it a mutton broth and some cheese in the bowl with it? “This is peak peasant food. One detail that I love is there are twice as many sheep as humans on the island of Sardinia. Here you have a young sheep’s milk cheese that just melts into the mutton broth. “And what I really love about this is that the ingredients are so humble, but it’s such a labor of love. It’s just like the ultimate act of service. “And for over 300 years, only women in this one family knew how to make it. This knowledge was a closely kept secret that was passed down through a single matriarchal line. And the sort of OG master of the family is named Paola Abraini. “For each festival, she spends five hours a day for a month prepping pasta. So there’s enough to feed 1,500 pilgrims.” The crazy thing to me about this is that there are more than, what, 300 shapes of pasta in Italy. And this feels like one of the only ones that has never really spread beyond its place of origin. Like tortellini, which I think are supposed to look like Venus’s navel, weirdly, were invented in Bologna. And orecchiette, or little ears, are from Pu

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

What if I told you there was a pasta so special that for more than 300 years pilgrims on the Italian island of Sardinia have trekked 20 miles through the dark just to have a single bowl? What if I told you this pasta was so fiendishly complicated to make that it’s thwarted celebrity chefs and the world’s biggest pasta company?

For generations, the art of how to make su filindeu, or threads of god, has been a closely guarded secret. Only women in the small city of Nuoro were allowed to learn this craft. Each mother would teach her daughter how to make these mysterious noodles.

But as so often happens with things over the generations, the number of women who possess this particular knowledge has dwindled. A few years ago you could count all of them on one hand. It looks like the threads of god might vanish forever.

I’m Johanna Mayer and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places.

Today, the story of the world’s rarest and most mysterious pasta. What it is, why it is so sought after, and what might save it from extinction after this. I’m here today with Diana Hubbell. She’s a reporter for Atlas Obscura and she wrote a piece about su filindeu.

Diana, hello. Welcome back.

“Hi, happy to be here and talking about my favorite subject, which obviously is noodles.”

Obviously. So tell me about these noodles. What exactly is su filindeu?

“Su filindeu, which literally translates as ‘threads of god’ in Sardo—which is actually closer to Latin than it is to modern day Italian—it’s this type of incredibly fine hand-pulled noodle. If you’ve seen Chinese chefs make Lanzhou-style ramen, the process actually looks weirdly similar. The cook kneads out a ball of dough until elastic, then stretches it out between their hands, then loops it back over and stretches it again. So, you go from two strands to four to eight, all the way up until 256 strands.”

Do we know, is there any significance to that 256 number or is it just like the next time they pulled it, it all broke apart?

“I wish I had a more satisfying answer, but I’m pretty sure that when they tried to double it again, just—there was no hope.”

That was the breaking point, yes. It feels like there must be some sort of secret Sardinian magical ingredient that keeps these strands from breaking.

“So, I was convinced of that going into this story, but it is really just semolina flour, water, and sea salt. There’s no eggs, there’s no special flour.

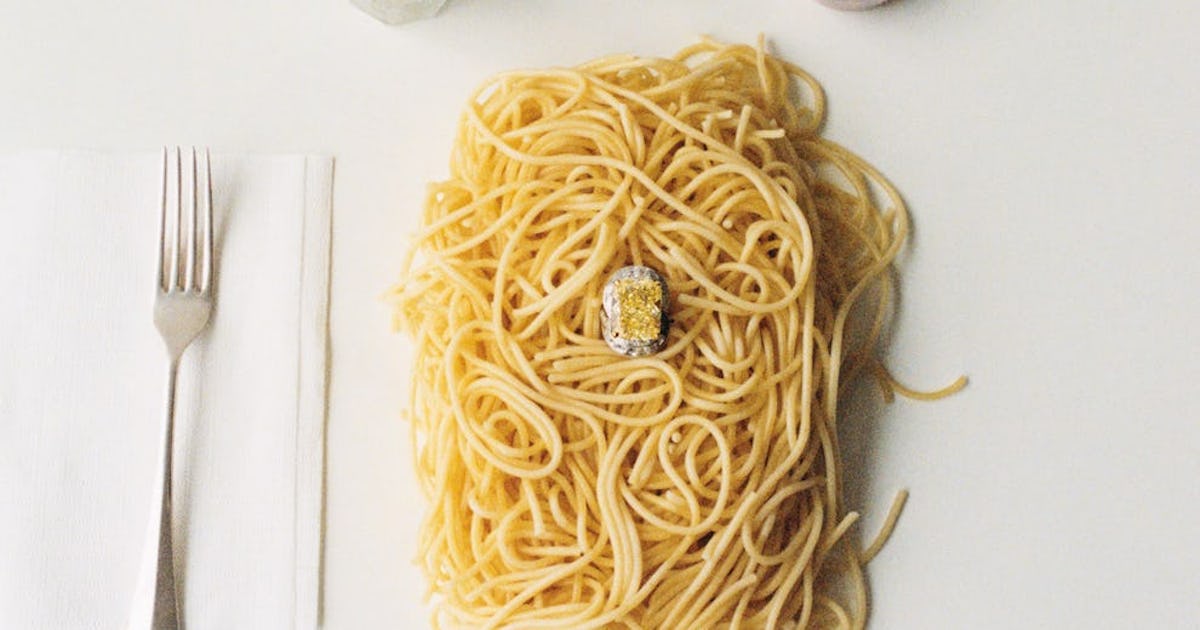

“And for context, su filindeu makes angel hair look chunky. These are thicker than a human hair, but not by a lot. So you can sort of picture it better. This is not just the world’s thinnest spaghetti. Because I think if you just boiled these incredibly long, thin noodles as they are, they would just disintegrate. They’re so fragile.

“So what they do is they stretch them all out and they lay them over this huge wooden disc called a fondo. And then they take the next batch of 256 and they stretch it crisscrossed atop. And then they allow that to dry together in the sun and then break it all into shards.

“The final result looks almost like this ethereal, super delicate version of Chex Mix.”

That sounds good, honestly. Texturally, I imagine—sort of chewy.

“Slight factual note. It’s so thin, it’s actually very wispy. It almost dissolves in your mouth.”

It’s not chewy?

“Not chewy.”

Okay. Noted. I stand corrected.

And so this is what Christian pilgrims are walking 20 miles through the night to eat.

“Yep. Twice a year on the Feast of San Francesco, they walk from Nuoro to the village of Lula. And to celebrate their devotion when they arrive, they’re given a warm foot bath and a bowl of this beautiful handmade pasta at the end of their journey.”

And it’s served super simply, right? Is it a mutton broth and some cheese in the bowl with it?

“This is peak peasant food. One detail that I love is there are twice as many sheep as humans on the island of Sardinia. Here you have a young sheep’s milk cheese that just melts into the mutton broth.

“And what I really love about this is that the ingredients are so humble, but it’s such a labor of love. It’s just like the ultimate act of service.

“And for over 300 years, only women in this one family knew how to make it. This knowledge was a closely kept secret that was passed down through a single matriarchal line. And the sort of OG master of the family is named Paola Abraini.

“For each festival, she spends five hours a day for a month prepping pasta. So there’s enough to feed 1,500 pilgrims.”

The crazy thing to me about this is that there are more than, what, 300 shapes of pasta in Italy. And this feels like one of the only ones that has never really spread beyond its place of origin.

Like tortellini, which I think are supposed to look like Venus’s navel, weirdly, were invented in Bologna. And orecchiette, or little ears, are from Puglia. But those are everywhere. Like, I can go to the grocery store right now and buy them. But threads of God, as far as I’ve heard, is one of the only ones, if not the only one, that just never made it out.

“And that’s actually not for lack of trying. Barilla tried to make a machine that would churn out su filindeu, and they completely failed. Like, we’re talking the world’s biggest pasta company, and they just couldn’t do it. And then Jamie Oliver went over to try and learn how to make it and, again, failed spectacularly on camera, which you can watch on YouTube.”

I will be watching that on YouTube after this. Honestly, I love that. The biggest pasta company on earth with the most resources couldn’t do what Paolo was doing. It’s pretty funny.

Okay, so it’s not like anybody was necessarily hiding this recipe or keeping it secret or anything like that.

It’s just like, it’s really, really hard to make. And nobody can just figure it out without tons of training and practice and help and repetition. And for a long time, that’s kind of where we thought this story would end, right? We were left with this tiny handful of family members who could still make su filindeu, and they were all sort of growing older and time was running out.

“It didn’t look good. The youngest of these women is in her 50s. Paola’s in her 60s. But then things started to shift in part because of, I think this is a story where the people writing about the thing influenced the future of it. So in 2016, Eliot Stein, who is a journalist for the BBC living in Sardinia, heard about su filindeu, and he wrote about it.

“And a big part of this was because Paola herself made a decision consciously to speak with outsiders and share this closely guarded knowledge for the first time in generations.”

She wanted to save it, it sounds like.

“Yeah, exactly. She saw the writing on the wall, and she didn’t want this very rare craft that meant so much to her family to die. And then word started to get out because of the nature of the internet, and chefs started to hear about it. I actually spoke with one who went to Sardinia and managed to recreate it.”

Not Jamie Oliver.

“Not Jamie Oliver. There are actually a few chefs who’ve managed it at this point. And even though men historically weren’t supposed to make it, Luca Flores and Noro has learned the skill, and Lee Yum Hwa in Singapore. I spoke with Rob Gentile, who’s an Italian-Canadian chef at the restaurant Stella in Los Angeles.

“And right around the pandemic, he saw something about su filindeu online, and he just became completely obsessed. Then in October 2021, he arranged to visit Paola with another chef, David Marcelli. This is how he first describes meeting her.”

“The first introduction to su filindeu was literally like a ceremony. She was like, first we have to have a social moment, and let’s have coffee, let’s have some biscotti. But she wanted to get to know us, and it was just this personal thing. It was a personal introduction. It was special, and I could tell these people took it very seriously, you know?”

“So, Rob told me all about the process and his experience with Paola, and it reminded me of every Italian cooking teacher specifically I’ve ever had. She doesn’t measure anything.”

Classic.

“She just knows it is in her bones at this point.”

“Watching her make it is like magic. The amount of perfection in her movement, it’s wild. She was lovely, and she was joyful and laughing and, you know, like it’s easy. And she’s like, you know, all you gotta do is just practice. It takes time.”

“So easy, just pulling strands of pasta into 256 strands the width of a human hair. So easy. Yeah, no big deal. But eventually, after about three hours or so, they’re able to produce a batch, and they’re so excited. And so he goes back to his restaurant in Los Angeles and is going to show everyone this pasta—and it doesn’t work at all.”

No! Wait, what happened?

“The dough, it just keeps breaking, which is what I think would happen to most people. And it only starts working when he imports that exact type of semolina flour from Sardinia.”

Did he figure out what it was exactly?

“I suspect it has something to do with the gluten content, but he doesn’t know. And he phrased it to me that there’s something sacred about this pasta, that even sort of in a more controlled restaurant kitchen environment, he doesn’t quite understand it. He’s able to do it, but it remains sort of mystical.”

What’s the deal with this now? Does it change what this pasta means if you can just go to a restaurant in LA and pay for it? Does it lose anything?

“I sort of feel that way. I felt very conflicted about this story. I think Paola is grateful that it is going to survive for future generations. I’m glad that there’s more interest in this dying art that wasn’t even very well known outside of Sardinia before.

“But from what I’ve heard, there are some mixed feelings within the Abraini family about commercializing the pasta. I think there’s a bit of a rift there. And I understand.”

I have to say, though, if I saw a su filindeu on a menu at a restaurant, especially hearing this, I’m sure that I would order it.

But that’s kind of also not the way that I really want to experience it. I want to go to Sardinia. I want to trek through the night. I want the footbath.

“You need the footbath. You need the footbath.”

Essential part of this experience.

“Yeah, for me, so much about this is: Work is an act of devotion. It’s about the craft, but it’s also about—it’s a non-commercial exchange. You’re doing an act of service and they’re providing an act of service. And so, yeah, I would also order it on a restaurant menu for sure. But really, I just want to go to Sardinia and maybe make a small pilgrimage. They welcome everyone.”

Thanks, Diana.

“Yeah, thanks so much. This was great.”

Diana Hubbell is a reporter at Atlas Obscura. She’s done a lot of reporting on su filindeu. We’ll put a link in our episode description.

Su filindeu is now on the menu at a handful of restaurants across the world, including Lee Yum Hwa’s private dining outfit, Ben Fatto 95 in Singapore, and Rob Gentile’s restaurant Stella in LA.

Honestly, still pretty rare and still a labor of love. But if you want the OG version from Paola, you gotta head to Sardinia during the Feast of San Francesco and trek 20 miles through the night. Enjoy that footbath. Also, this actually isn’t the first time that Atlas Obscura has reported on the threads of God.

There’s an entry all about it in our Gastro Obscura book, which was published in 2021. At the time, Paola and her family were still the only ones making the threads of God. And we only learned about this new development, about it spreading outside, when a reader left a comment on one of our stories saying, hey, this actually isn’t true anymore.

So thank you for the tip. And please keep talking to us. You can always send us an email at hello@atlasobscura.com.

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Our podcast is a co-production of Atlas Obscura and Stitcher Studios.

The people who make our show include Dylan Thuras, Doug Baldinger, Chris Naka, Kameel Stanley, Manolo Morales, Baudelaire, Amanda McGowan, Alexa Lim, Casey Holford, and Luz Fleming. If you like our show, please subscribe and leave us a good review.

We really appreciate it. I’m Johanna Mayer. See you next time.

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)