Park of the Canals in Mesa, Arizona

Despite its arid climate, agriculture flourished in Arizona’s Salt and Gila River valleys for thousands of years. The Hohokam Native Americans initially used floodwater farming to grow corn, beans, and squash close to the rivers. By the 7th century, communities built a system of giant canals at a scale not seen anywhere else in the Americas. The longest was 20 miles, with the whole network reaching up to 1,000 miles. Some near S’edav Va’aki were up to 85 feet wide and 20 feet deep. This allowed over 110,000 acres of land to be irrigated around Phoenix. With over 30,000 people, the area became the largest population in the southwestern United States. The canals had specialized features such as weirs that directed water into them, and head gates that limited how much water entered them. They were able to maintain a constant flow rate and had a gradient of only a few feet per mile. As such, they were not prone to erosion or silt deposition. The political cooperation necessary to build and maintain the canals has been a matter of speculation today. The canals were not dug with shovels, but wooden sticks and stone “hoes” without handles that were used to loosen the soil, which was then removed by hand. One mystery that remains is why and how these canals were abandoned in the 15th century. Some theories include a drought, the population straining the water supply, and fields becoming too saline. Today, the Hohokam's descendants, the O’odham people, continue to practice agriculture on a smaller scale. Settlers crossing the United States were astonished by the then-dry canals. They realized that an agricultural civilization of immense complexity resided in the Salt River Valley, and named the city of Phoenix to reflect their hopes that a new settlement would rise from the ancient Hohokam ones. Settlers even began to reuse the canals for water once again. The Mormon founders of the City of Mesa were initially told that they could not channel water to their town, but instead found and used an ancient canal for irrigation. Today, many aqueducts in the Phoenix area follow the route of Hohokam canals, or were even constructed from the ancient canals themselves. A portion of several interconnected canals, including one repurposed by Mormons only to again be abandoned, have been preserved at the Park of the Canals. A single path gives a view of the eroded canal ruins. Unfortunately, there are few descriptions on site and vegetation obscures some of what is left. But, one can use their imagination to picture how the canals were built and how they delivered water to a vast agricultural society over 500 years ago. The grounds are also home to botanical garden, exploring the history of the natural landscape.

Despite its arid climate, agriculture flourished in Arizona’s Salt and Gila River valleys for thousands of years. The Hohokam Native Americans initially used floodwater farming to grow corn, beans, and squash close to the rivers. By the 7th century, communities built a system of giant canals at a scale not seen anywhere else in the Americas. The longest was 20 miles, with the whole network reaching up to 1,000 miles. Some near S’edav Va’aki were up to 85 feet wide and 20 feet deep. This allowed over 110,000 acres of land to be irrigated around Phoenix. With over 30,000 people, the area became the largest population in the southwestern United States.

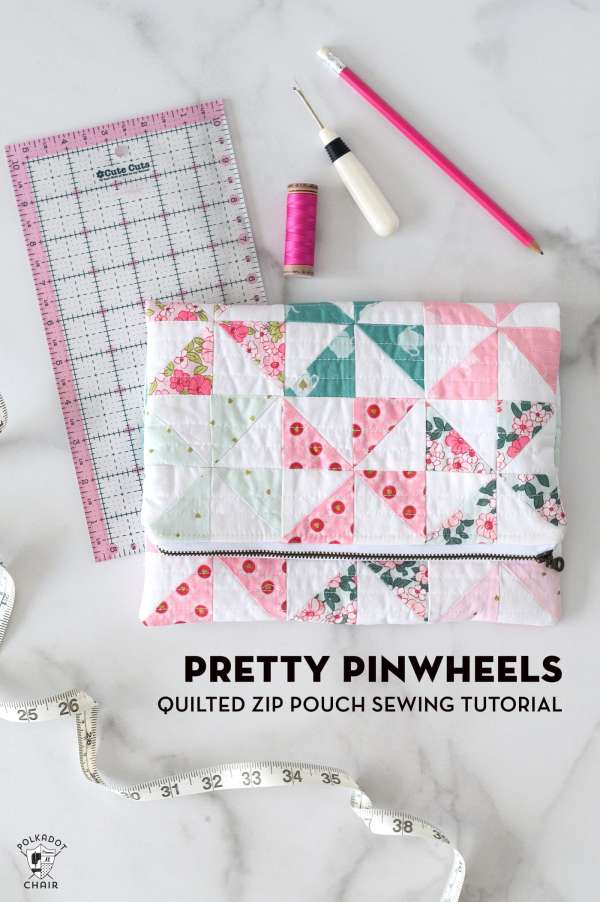

The canals had specialized features such as weirs that directed water into them, and head gates that limited how much water entered them. They were able to maintain a constant flow rate and had a gradient of only a few feet per mile. As such, they were not prone to erosion or silt deposition. The political cooperation necessary to build and maintain the canals has been a matter of speculation today. The canals were not dug with shovels, but wooden sticks and stone “hoes” without handles that were used to loosen the soil, which was then removed by hand.

One mystery that remains is why and how these canals were abandoned in the 15th century. Some theories include a drought, the population straining the water supply, and fields becoming too saline. Today, the Hohokam's descendants, the O’odham people, continue to practice agriculture on a smaller scale.

Settlers crossing the United States were astonished by the then-dry canals. They realized that an agricultural civilization of immense complexity resided in the Salt River Valley, and named the city of Phoenix to reflect their hopes that a new settlement would rise from the ancient Hohokam ones. Settlers even began to reuse the canals for water once again. The Mormon founders of the City of Mesa were initially told that they could not channel water to their town, but instead found and used an ancient canal for irrigation. Today, many aqueducts in the Phoenix area follow the route of Hohokam canals, or were even constructed from the ancient canals themselves.

A portion of several interconnected canals, including one repurposed by Mormons only to again be abandoned, have been preserved at the Park of the Canals. A single path gives a view of the eroded canal ruins. Unfortunately, there are few descriptions on site and vegetation obscures some of what is left. But, one can use their imagination to picture how the canals were built and how they delivered water to a vast agricultural society over 500 years ago.

The grounds are also home to botanical garden, exploring the history of the natural landscape.